Difference between revisions of "Construction and demolition waste"

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

The definition of hazardous/special waste is relatively wide and covers objects that contain hazardous substances such as televisions and fluorescent light tubes. As a result, many companies are likely to produce some form of waste that is hazardous and need to deal with it accordingly. | The definition of hazardous/special waste is relatively wide and covers objects that contain hazardous substances such as televisions and fluorescent light tubes. As a result, many companies are likely to produce some form of waste that is hazardous and need to deal with it accordingly. | ||

| − | The European Waste Catalogue<ref name="no7"> | + | The European Waste Catalogue<ref name="no7">European Waste Catalogue. List of wastes pursuant to Article 1(a) of Directive 75/442/EEC on waste and Article 1(4) of Directive 91/689/EEC on hazardous waste</ref> (EWC) contains a list of all types of waste and each waste type is given a six-digit code. Hazardous waste is identified in the EWC with an asterisk (*): |

*Some wastes, called 'absolute entries', are always classed as hazardous, for example inorganic wood preservatives, waste paint or varnish remover and wastes from asbestos processing | *Some wastes, called 'absolute entries', are always classed as hazardous, for example inorganic wood preservatives, waste paint or varnish remover and wastes from asbestos processing | ||

*Other wastes, called 'mirror entries', are classed as hazardous if they are present in amounts above certain threshold concentrations, for example some wastes containing arsenic or mercury. | *Other wastes, called 'mirror entries', are classed as hazardous if they are present in amounts above certain threshold concentrations, for example some wastes containing arsenic or mercury. | ||

Revision as of 12:09, 12 March 2019

The construction and demolition sectors are under increasing pressure to improve performance, reduce waste and increase recycling in a drive towards the circular economy. Reducing waste is a priority for the European Union and the UK Government and there are many new regulations, measures and targets to reduce waste within the construction industry. For example, the UK Strategy for Sustainable Construction [1] included a target to reduce construction, demolition and excavation (CD&E) waste going to landfill by 50% compared to 2008 levels by 2012.

Steel construction products and technologies are inherently low waste through all stages of the building life cycle; production, construction and end-of-life of buildings. This article explains the measures introduced to reduce CD&E waste and sets out steel’s credentials as a low waste construction material. Image does not exist

[top]Background

In 2011, WRAP estimated that over 100 million tonnes of inert construction, demolition and excavation (CD&E) waste was being generated each year in England[3]. In addition, an estimated 20 million tonnes of unused waste was going to landfill. CD&E waste is also a major component of fly-tipped waste and is estimated by the Environment Agency to be responsible for around one third of all fly tipping incidents.

Research commissioned by WRAP suggests that 10 – 30% of the construction materials that end up as waste on site have never actually been used and that the true cost of construction waste can be up to 15 times more than the waste disposal (skip hire) costs when labour and material costs are taken into account. The construction industry therefore is increasingly coming under pressure to improve resource efficiency and reduce waste. The revised Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC)[4] came into force on 12 December 2008. Article 40 requires EU member states to bring into force the laws, regulations and administrative provisions necessary to comply with this Directive.

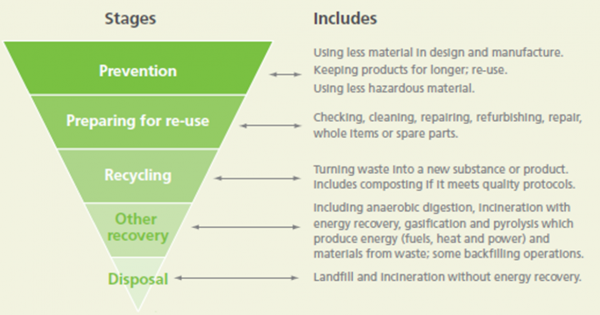

The Directive requires the UK to design and implement waste prevention programmes and sets the challenging target to reuse and recycle 70% of construction and demolition waste by 2020. Such programmes have needed to take account of the five-step hierarchy shown.

Reducing waste is a priority for the UK Government. The Waste Strategy for England[5] set out a number of key objectives and targets to reduce material consumption and waste and to break the link between economic growth and waste. In line with the above waste hierarchy, the Government’s objectives in relation to construction waste are:

- To provide the drivers for the construction sector to improve its economic efficiency by creating less waste at every stage of the supply chain, from design to demolition;

- To encourage the sector to treat waste as a resource, closing the loop by re-using and recycling more and asking contractors for greater use of recovered material; and

- To improve the economics of the re-use and recycling sector by increasing sector demand and securing investment in the treatment of waste – this will benefit all waste streams, including construction.

The UK Strategy for Sustainable Construction[1] was published in June 2008. The Strategy included the target to reduce CD&E waste to landfill by 50% by 2012 compared to 2008 levels. Specific actions to help deliver this target included:

- Individual companies signing up to the WRAP Construction Waste Commitment

- Establishing sector resource efficiency plans

- Setting an overall target for the diversion of demolition waste from landfill

- Extending the Plasterboard Voluntary Agreement to the rest of the supply chain

- Reducing construction packaging waste by 20%.

In 2013, the Government claimed that the target to reuse and recycle 70% of construction and demolition waste by 2020 had already been achieved[6].

[top]Regulations and other drivers

To help to achieve the UK’s waste reduction targets, a number of measures have been introduced to reduce and manage waste through all stages of the design, construction and at the end-of-life of buildings. These apply to designers and construction and demolition contractors.

[top]Duty of Care Regulations

Construction companies have a legal ‘duty of care’[7] with respect to any waste that they generate on site. This duty applies to anyone who produces, imports, transports, stores, treats or disposes of controlled waste from business or industry. Commercial, industrial and household wastes (including hazardous/special wastes) are classified as ‘controlled waste’. The duty of care also applies to anyone who acts as a waste broker. Companies must ensure that:

- Their waste is stored, handled, recycled or disposed of safely and legally

- Their waste is stored, handled, recycled or disposed of only by businesses which hold the correct, current licence to do the work

- They record all transfers of waste between their and another business, using a waste transfer note (WTN) signed by both businesses

- They keep all WTNs for at least two years

- They record any transfer of hazardous/special waste between their business and another business, using a consignment note signed by both businesses

- They keep all consignment notes for at least three years.

If the company is a sub-contractor and the main contractor arranges for the recovery or disposal of waste that they produce, the sub-contractor is still responsible for those wastes under the duty of care.

This duty of care has no time limit. It extends until the waste has either been finally disposed of or fully recovered.

If companies produce or deal with waste that has certain hazardous properties, they will also have to comply with the hazardous/special waste regulations.

[top]Hazardous/Special Waste Regulations

Waste that has hazardous properties which may make it harmful to human health or the environment is known as hazardous waste[8] in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and special waste in Scotland.

The definition of hazardous/special waste is relatively wide and covers objects that contain hazardous substances such as televisions and fluorescent light tubes. As a result, many companies are likely to produce some form of waste that is hazardous and need to deal with it accordingly.

The European Waste Catalogue[9] (EWC) contains a list of all types of waste and each waste type is given a six-digit code. Hazardous waste is identified in the EWC with an asterisk (*):

- Some wastes, called 'absolute entries', are always classed as hazardous, for example inorganic wood preservatives, waste paint or varnish remover and wastes from asbestos processing

- Other wastes, called 'mirror entries', are classed as hazardous if they are present in amounts above certain threshold concentrations, for example some wastes containing arsenic or mercury.

The environmental regulator, this is the Environment Agency in England and Natural Resources Wales in Wales, tracks the movement of hazardous waste through the consignment note system. This ensures that waste is managed responsibly from where it is produced until it reaches an authorised recovery or disposal facility. Companies must ensure that all hazardous waste is stored and transported with the correct packaging and labelling.

Hazardous waste can only be disposed of at a landfill site that is authorised to accept it. Some landfill sites that are classified as non-hazardous may be able to take certain stable non-reactive hazardous wastes if they have the appropriate facilities. A landfill site authorised to accept hazardous waste may not be able to take all types of hazardous waste.

Hazardous waste must be treated, before it can be sent to landfill, to meet the limits set by a landfill site's waste acceptance criteria (WAC). Treatment means physical, thermal, chemical or biological processes, including sorting, that change the characteristics of the waste in order to:

- Reduce its volume

- Reduce its hazardous nature

- Make it safe to handle

- Make it easier to recover.

For further information on current legislation with respect to construction waste see the Environment Agency guidance.

[top]Landfill Tax and Aggregates Levy

Introduced in 1996, the Landfill Tax remains the primary fiscal incentive to promote good waste management practice in the UK. The tax rose by £8 per tonne each year from 2007 up until 2014 and the standard rate was £80 per tonne at April 2014 for non-hazardous (and non-inert) wastes. The Government then announced that from 2015-16 it would rise in line with inflation and in 2017 it was £86.10 per tonne. A lower rate of £2.70 per tonne applied to inactive (or inert) waste at the same time.

Reflecting the large volume of aggregates consumed by the construction industry (over 200 Mt pa), the Aggregates Levy was introduced in 2002 to reduce demand for primary aggregates and to encourage the use of recycled and secondary aggregates. In 2017 the levy was £2.00 per tonne of primary aggregates.

[top]Site Waste Management Plans Regulations (SWMP)

Effective construction site waste management is a key tool for improving efficiency and reducing waste. Introduced in April 2008, the SWMP Regulations[10] made it compulsory to develop and implement SWMPs on construction projects costing more than £300k. Defra guidance[11] advised that a SWMP should:

- Identify the different types of waste that will be produced by the project, and note any changes in the design and the materials specification that seek to minimise this waste

- Consider how to re-use, recycle or recover the different wastes produced by the project

- Require the construction company to demonstrate that it is complying with the duty of care regime

- Record the quantities of waste produced.

The Regulations also required a more detailed analysis to be conducted on projects costing more than £500k.

Although the Site Waste Management Plans Regulations Act 2008 was repealed on the 1st December 2013 as part of Government’s Red Tape Challenge, SWMPs continue to be used on many construction sites and by responsible contractors.

[top]BREEAM

BREEAM is BRE’s Environmental Assessment Method for buildings. Under BREEAM, credits are awarded under a number of environmental categories, one of which is waste, and the buildings rated according to its total score.

Under BREEAM 2014[12] the following waste issues are assessed:

- Construction waste management (Wst 01 – see below)

- Use of recycled or secondary aggregates (Wst 02)

- Operational waste - Provision of dedicated storage facilities for recyclable waste streams within new buildings (Wst 03)

- Specification and fitting of floor and ceiling finishes selected by the building occupant (Wst 04)

- Adaptation to climate change - To recognise and encourage measures taken to mitigate the impact of extreme weather conditions arising from climate change over the lifespan of the building (Wst 05)

- Functional adaptability - To recognise and encourage measures taken to accommodate future changes of use of the building over its lifespan (Wst 06).

BREEAM does not specifically address any issues in connection with demolition waste reduction or management although credit Wst 2 does encourage the use of recycled and secondary aggregates.

The most highly weighted waste issue under BREEAM is Construction waste management (Wst 01) under which credits are awarded according to the benchmarks shown in the table.

| BREEAM credits | Amount of waste generated per 100m2 (gross internal floor area) | |

|---|---|---|

| Volume (m3) | Weight (tonnes) | |

| One credit | 13.3 | 11.1 |

| Two credits | 7.5 | 6.5 |

| Three credits | 3.4 | 3.2 |

| Exemplary level | 1.6 | 1.9 |

The only minimum construction waste requirement under BREEAM is that one (of 4) Wst 01 credit is required to obtain an ‘Outstanding’ rating.

Where there are existing buildings on the site being developed, it is a requirement under Wst 01 that a pre-demolition audit be undertaken.

A further credit is available under Wst 01 where it can be demonstrated that a significant proportion of non-hazardous C&D waste generated by the project, has been diverted from landfill.

| BREEAM credits | Type of waste | Volume (%) | Tonnage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| One credit | Non demolition | 70 | 80 |

| Demolition | 80 | 90 | |

| Exemplary level | Non demolition | 85 | 90 |

| Demolition | 85 | 95 |

BREEAM also accounts for construction waste through the assessment of materials using the Green Guide to Specification.

[top]Green Guide to Specification

BREEAM uses the Green Guide to Specification[13] to assess the environmental impacts of construction materials and products. The life cycle assessment methodology used by the Building Research Establishment (Environmental Profiles ) to derive the Green Guide ratings, takes account of waste during the production and construction stages.

[top]Waste and Resources Action Programme (WRAP)

WRAP has worked to set standards for good practice in waste and resource management for the CD&E sector. WRAP has provided free access to tools and know-how so that construction projects could make best use of materials resource.

In 2008, WRAP launched its Halving Waste to Landfill (½W2L) campaign. ½W2L was a voluntary agreement that provided a framework through which industry could support and deliver against the target of halving waste to landfill by 2012.

Initially, around 700 companies from all parts of the construction industry signed up to the campaign which required them to:

- Set a specific target for reducing waste to landfill

- Embed the target in corporate policy and processes

- Set corresponding requirements in project procurement and engage with their supply chain

- Measure performance relative to a corporate baseline

- Report annually on overall corporate performance.

In 2015, WRAP announced that over 800 companies had signed the commitment to reduce waste leading to 5 million tonnes of waste per year diverted from landfill and £400 million cost savings per year realised by the companies involved.

At the same time however, it announced its intention to focus its future efforts on resource management, food sustainability and product sustainability.

[top]ICE demolition protocol

The ICE Demolition Protocol[14] provides an overarching framework which enables the waste hierarchy to inform approaches for managing buildings and structures at the end of their lives. First launched in 2003, the Demolition Protocol has been adopted and implemented across a range of public and private sector projects and is included in Supplementary Planning Guidance in a number of Local Authorities.

The Protocol describes the overarching implementation approaches for Materials Resource Efficiency (MRE) associated with demolition and construction activities, with a decision-making framework which emphasises the need to reuse, then recycle, with landfill as a last resort. It provides a number of overarching methodologies which include:

- Providing a Deconstruction/Demolition Recovery Index (DRI) – this is the percentage of building elements, products or materials to be reused or recycled

- Estimating bulk quantities through a pre-demolition audit, summarised in a Demolition Bill of Quantities (D-BOQ)

- Providing a new build recovery index (NBRI) – describing the percentage of building elements, products or materials recovered for use in the new build

- Demonstrating compliance with Site Waste Management Plan requirements

- Describing how carbon benefits, through avoided haulage movements, can be realised and estimated easily

- Providing data for in-house and local authority monitoring of annual construction and demolition waste arisings.

[top]C&D waste management tools

The BRE has developed a suite of SMARTWaste tools and associated consultancy services, to measure, manage and reduce construction and demolition waste.

[top]Waste in steel construction

Steel construction products are inherently low waste products through all phases of the design, production, construction and deconstruction process. Designers and specifiers can be confident that, by choosing steel construction products and systems, material resources are optimised, waste is minimised and recycling is maximised.

[top]Steel production

By-products from iron and steel making, including sludges, slags and dust, are beneficially used by the construction industry in a range of products including roadstone, lightweight aggregate and as a substitute for Portland cement. Tata Steel, the major steel producer in the UK, recycles or reuses over 90% of its process residues.

Approximately 3 million tonnes of blast furnace slag is produced in the UK annually. Of this around 75% is quenched and this is then processed to produce ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS), which is used by the concrete industry as a cement replacement material. The remainder is air-cooled and is used as an aggregate. The split between the two uses is dictated by production choices, economics and demand.

[top]Manufacture

During component manufacture, computer controlled, fully or semi-automated production lines ensure that wastage of steel is minimised. The typical wastage rate for fabricating structural steel products is just 4% and any off-cuts, trimmings, swarfe, etc. from the production process are 100% recycled into new steel. For steel cladding and decking products, wastage rates are typically 1.5 – 2% and around 1.8% for secondary structural products such as rails, purlins, studs, etc.

[top]Construction

Steel products are delivered to the construction site pre-engineered to the correct dimensions; consequently there is no site waste. Furthermore the quality of factory produced steel construction products and the dimensional stability of the material itself, means that there are few defects and hence little site waste. Steel products are delivered to site with minimal packaging. Packaging comprises mainly timber pallets and bearers and plastic or metal strapping. Timber packaging is generally reused by the haulage company making site deliveries and the strapping is either recycled or reused.

[top]Deconstruction

When a building is deconstructed, the ease with which steel construction products can be reclaimed, coupled with the economic value of scrap steel, means that virtually all steel is recovered and either reused or recycled. Currently 96% of steel from deconstructed buildings in the UK is recovered.

[top]Designing out waste

To date the focus of C&D waste reduction has been mainly on site waste management practice. Arguably however, the best opportunities for improving materials resource efficiency in construction projects occur during the design stage. Implementing these opportunities can provide significant reductions in cost, waste and carbon.

There are five key principles that design teams can use during the design process to reduce waste. These principles are based on extensive consultation, research and work carried out by WRAP[15] directly with design teams . They are summarised below together with questions the design team should address to design out waste.

[top]Design for reuse and recovery

Design for reuse of material components and/or entire buildings has considerable potential to reduce the environmental burdens from construction. Much of this is common sense as, with reuse, the effective life of the materials is extended and thus annualised burdens are spread over a greater number of years. Reuse, in the waste hierarchy is generally preferable to recycling, where additional processes are involved, some of which will have their own environmental burdens.

Key questions for the design team include:

- On previously developed sites, can materials from demolition of the building be reused in the design?

- Can reclaimed products or components be reused?

- When materials are reused, can they be reused at their highest value?

- Can any excavation materials be reused?

- Can cut and fill balance be achieved? How can it be optimised to avoid removal of spoil from site?

In addition to considering reuse of previously developed sites, designers are encouraged to think about how their new buildings can be designed in ways that they can be dismantled more easily for reuse and recovery in the future.

[top]Design for off-site construction

The benefits of off-site factory production in the construction industry are well documented and include the potential to considerably reduce waste especially when factory manufactured elements and components are used extensively. Its application also has the potential to significantly change operations on site, reducing the amount of trades and site activities and changing the construction process into one of a rapid assembly of parts that can yield many benefits including:

- Reduced construction related transport movements;

- Improved health and safety on site through avoidance of accidents;

- Improved workmanship quality and reducing on site errors and re-work, which themselves cause considerable on site waste, delay and disruption; and

- Reduced construction timescales and improved programmes.

Off-site construction is one of a group of approaches to more efficient construction sometimes called Modern Methods of Construction (MMC) that also include prefabrication and improved supply chain management. Technologies used for off site manufacture and prefabrication include light gauge steel framing systems and modular and volumetric forms of construction which offer great potential for improvements to the efficiency and effectiveness of UK construction.

To assess the suitability of off-site construction, design teams should consider the following questions:

- Can the design or any part of the design be manufactured off site?

- Can site activities become a process of assembly rather than construction?

Experience shows that the choice of off-site construction can have a significant influence on initial design considerations and therefore should be considered during the early project stages. Key considerations with respect to the choice of off-site construction include:

- Space planning, especially structural and planning grids

- Structural design/system selected

- Project buildability

- Procurement routes

- Consideration of how aesthetics are affected by off-site construction.

[top]Design for materials optimisation

Good practice in this context means adopting a design approach that focuses on materials resource efficiency so that less material is used in the design, i.e. lean design, and/or less waste is produced in the construction process, without compromising the design concept.

Three main areas offer significant potential for waste reduction

- Minimisation of excavation

- Simplification and standardisation of materials and component choices

- Dimensional coordination.

In order to assess the best project opportunities for material optimisation, the following key questions need to be answered by the design team:

- Can the design, form and layout be simplified without compromising the design concept?

- Can the design be coordinated to avoid/minimise excess cutting and jointing of materials that generate waste?

- Is the building designed to standard material dimensions?

- Can the range of materials required be standardised to encourage reuse of offcuts?

- Is there repetition & coordination of the design, to reduce the number of variables and allow for operational refinement, e.g. reusing formwork?

[top]Design for waste efficient procurement

Designers have considerable influence on the construction process itself, both through specification as well as setting contractual targets, prior to the formal appointment of a contractor/constructor. Designers need to consider how work sequences affect the generation of construction waste and work with the contractor and other specialist subcontractors to understand and minimise these. Once work sequences that cause site waste are identified and understood, they can often be ‘designed out’.

Key questions for the design team include:

- Has research been carried out to identify where on site waste arises?

- Can construction methods that reduce waste be devised through liaison with the contractor and specialist subcontractors?

- Have specialist contractors been consulted on how to reduce waste in the supply chain?

- Have the project specifications been reviewed to select elements/components/materials and construction processes that reduce waste?

[top]Design for deconstruction and flexibility

Designers need to consider how materials can be recovered effectively during the life of the building when maintenance and refurbishment is undertaken or when the building comes to the end of its life.

There are a number of barriers to large scale reuse of materials and components in the construction industry. Perhaps the greatest difficulty in applying design for deconstruction and flexibility however, is the time frame involved, which is very often longer than the financial and professional involvement of the client and design team. As buildings are sold and re-sold over time, any connection between the original client and designer and the ultimate beneficiary of design for deconstruction and flexibility can become very remote.

Nevertheless, designing for future generations is embedded in the concept of long-term sustainable development and the circular economy. Not to design with design for deconstruction and flexibility in mind limits the future potential of design for reuse.

To assess the best project opportunities for reducing waste at deconstruction stage, the following key questions need to be addressed:

- Is the design adaptable for a variety of purposes during its life span?

- Can building elements and components be maintained, upgraded or replaced without creating waste?

- Does the design incorporate reusable/recyclable components and materials?

- Are the building elements/components/materials easily disassembled?

- Can a Building Information Modelling (BIM) system or building handbook be used to record which and how elements/components/materials have been designed for disassembly?

A range of alternative construction methods are likely to be suitable for design for deconstruction and flexibility. Generally, those methods that facilitate easy disassembly at the end of the design/service life to improve the potential for reuse and/ or recyclability should be selected in preference to the more contiguous structural systems. Reuse should invariably be chosen as a preferred end of life scenario rather than recycling. There is an added waste reduction benefit in the choice of such structural systems as they are likely to be fabricated using off-site construction and assembled on site.

Steel-framed buildings are inherently reusable and flexible.

As part of its programme to ‘design out waste’ WRAP produced a series of sheets of alternative design details which use less materials or result in less waste being created than ‘standard’ details used in construction. One of these design sheets[16] described the benefits of cellular steel beams. The table highlights the potential benefits of this form of construction identified by WRAP.

| Materials/waste | 25 – 50% reduction in steel weight in web (flanges unaffected). |

| Up to 15% reduction in M&E materials by passing straight through the web openings. | |

| Less material required for supporting elements (columns, foundations etc). | |

| Cost | Average savings of £38/metre for castellated steel beams. |

| Reduced savings for cellular beams due to more complex manufacture. | |

| Light weight can result in lower transportation costs. | |

| Further cost savings for supporting structure. | |

| Time | Long spans and light weight allow omission of some supporting structure leading to quicker construction. |

| Light weight also allows fewer deliveries and good manoeuvrability on site. | |

| Carbon | Potential steel embodied carbon savings of 41kg CO2e/metre compared to solid I-beams. |

| Other structural elements can also be lighter, reducing embodied carbon further. | |

| Recycling | Steel is 100% recyclable. |

| Manufacturing waste is recycled. | |

| Constructability | Light weight allows easy assembly. |

| Bolted sections are easy to assemble and disassemble. | |

| M&E services can pass through the beams. | |

| Replicability | Bespoke for individual projects – laser precision cutting ensures efficient manufacturing process. |

| Particularly suitable for long spans such as stadia, car parks and bridges |

[top]References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Strategy for Sustainable Construction; Department for Business, Enterprise & Regulatory Reform. June 2008

- ↑ CD&E WASTE: Halving Construction, Demolition and Excavation Waste to Landfill by 2012 compared to 2008

- ↑ The Construction Commitments: Halving Waste to Landfill Signatory Report 2011, WRAP

- ↑ Directive 2008/98/EC Of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on waste and repealing certain Directives

- ↑ Waste Strategy for England 2007, Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs

- ↑ Waste management plan for England. Published by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2013

- ↑ The Environmental Protection (Duty of Care) (England) (Amendment) Regulations 2003, Statutory Instrument 2003 No. 63

- ↑ The Hazardous Waste (England and Wales) Regulations 2005, Statutory Instrument 2005 No. 89

- ↑ European Waste Catalogue. List of wastes pursuant to Article 1(a) of Directive 75/442/EEC on waste and Article 1(4) of Directive 91/689/EEC on hazardous waste

- ↑ The Site Waste Management Plans Regulations 2008, Statutory Instrument 2008 No. 314

- ↑ Non-statutory guidance for Site Waste Management Plans. defra, 2008

- ↑ BREEAM UK New Construction, Non-domestic buildings (United Kingdom), Technical Manual, SD5076: 4.1 2014. BRE Global Ltd.

- ↑ The Green Guide to Specification, 4th ed., BRE and Oxford Brookes University, 2009

- ↑ Demolition Protocol; The Institution of Civil Engineers, 2008

- ↑ Designing out Waste: a design team guide for buildings, WRAP

- ↑ Designing out Waste: design detail sheet - Castellated and cellular beams, WRAP

[top]Resources

[top]Further reading

- Design for deconstruction. Principles of design to facilitate reuse and recycling CIRIA Report C607, 2004.

[top]See also

- Recycling and reuse

- Sustainable construction legislation, regulations and drivers

- BREEAM

- The Case for Steel

- The recycling and reuse survey

- Steel and the circular economy

[top]External links

- WRAP website on construction waste management

- BREEAM

- CIRIA: construction resources and waste management