Sustainable construction legislation, regulation and drivers

This article describes the sustainability legislation and regulations influencing UK building design and construction and some of the most significant other (non-mandatory or voluntary) drivers. The focus of this article is new non-domestic buildings although many of the measures described are equally applicable to domestic buildings.

In the UK the principle areas of legislation/regulation relating to sustainable buildings and sustainable construction practice include:

- Operational carbon emissions

- Building Assessment

- Waste

- Materials

- Planning.

Despite the significant number of initiatives relating to sustainable construction undertaken in the UK in recent years, there are only a few mandatory requirements. In addition, since the 2008 financial crisis, UK Government’s deregulatory and growth agendas have generally reduced the emphasis on regulation to drive sustainability in buildings and in the construction industry. More recently, growing appreciation of the need to tackle the climate change emergency, has seen the publication of many guides setting out how the UK construction industry can contribute to achieving national 2050 carbon reduction targets under the Climate Change Act. To date, legislation has not been introduced to enforce major carbon reductions from the construction and operation of buildings in the UK.

The impact of Brexit on EU-led initiatives impacting construction including energy efficiency, waste, building performance and circular economy, etc. is still to be seen.

In the absence of Government policy, there are a growing number of voluntary initiatives and guidance focussing on the circular economy and addressing the climate change emergency, particularly relating to greenhouse gas emissions reductions.

[top]The Paris Agreement and the UK Climate Change Act

The Paris Agreement, which was ratified by the UK in 2016, aims to limit increases in global average temperature to “well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” by the end of the century and to achieve this, has set the goal of achieving a ‘net zero’ carbon economy by around 2050. The UK Climate Change Act 2008 committed the Government to reducing the UK’s carbon emissions by 80% by 2050, from 1990 levels.

However, this target was made more ambitious in 2019 when the UK became the first major economy to commit to a ‘net zero’ target. The new target requires the UK to bring all greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050.

UK Government defines net zero as ‘achieving a balance between the amount of greenhouse gas emissions produced and the amount removed from the atmosphere. There are two different routes to achieving net zero, which work in tandem: reducing existing emissions and actively removing greenhouse gases.’

The Climate Change Act also provides a system of carbon budgeting, to help the UK meet its targets through a series of five-year carbon budgets. The UK is currently within the third carbon budget which runs from 2018 to 2022.

In line with the Climate Change Act, the UK Government’s Construction 2025[1] strategy, published in 2013, set a target of a 50% reduction in GHG emissions in the built environment, by 2025, from a 1990 baseline (in line with the fourth carbon budget).

Through the Clean Growth Grand Challenge, the government has set out its determination to maximise the advantages for UK industry from this global shift, including the mission to halve the energy use of new buildings by 2030.

[top]Operational carbon

Despite progress made over recent years, reduction of operational carbon emissions from buildings remains the primary sustainable construction driver in the UK.

Although the UK Government dropped its ambitious ‘zero carbon building’ targets in 2015, as part of its commitments under the Climate Change Act, the operational carbon performance of new and existing buildings remains an priority to achieve national targets by 2050.

The operation of buildings currently accounts for around 40% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions and therefore significant improvement in new and existing building performance is required if these targets are to be met.

Although some people argue that embodied carbon is now a priority, for most new, non-domestic buildings, operational carbon emissions over the whole building life cycle, remain the biggest carbon impact and therefore are the priority for further reductions. Cost effective operational carbon reductions are achievable using existing construction and renewable energy technologies.

One important reason why operational carbon remains the priority and biggest opportunity for further carbon reductions is the performance gap.

[top]The performance gap

There is significant evidence to suggest that buildings do not perform as well when they are completed, as was anticipated when they were designed; this difference between anticipated and actual performance is known as the performance or reality gap. Several recent studies have suggested that in-use energy consumption can be 5 to 10 times higher than compliance calculations, for example under Part L, carried out during the design stage.

More recently (2022), CIBSE has published TM63[2] which provides a framework to evaluate the performance use of buildings. TM63[2] aims to provide a methodological framework to undertake measurement and verification of building energy performance in-use.

[top]Part L of the Building Regulations

In England, the Government issues and approves Approved Document L (Conservation of fuel and power) to provide practical guidance on ways of complying with the energy efficiency requirements of the Building Regulations. In Wales, similar Approved Documents are published by the Welsh Government.

Approved Document L has evolved over recent years to implement the requirements of the EPBD at a national level and has a key role to play in reducing operational carbon emissions under the UK 2008 Climate Change Act.

The latest versions of Approved Document L were published in 2021. There has been criticism that Part L of the Building Regulations has lagged behind the Climate Change Act 2050 targets and trajectory. The 2021 Regulation changes have, to an extent, addressed this; requiring an average 27% improvement (relative to the previous 2013 edition of Part L) for non-domestic buildings and a 30% improvement for domestic buildings.

The intention of Approved Documents is to provide guidance on compliance with specific aspects of Building Regulations for some of the more common building situations. They set out what may be considered as reasonable provisions for compliance with the relevant requirements of the Building Regulations to which they refer. If Approved Documents are followed then there is a presumption that the requirements of the Building Regulations have been met, although this can be overturned. Approved Documents generally include a disclaimer that they may not be suitable for unusual buildings and also state that there is no requirement to adopt the solutions if it can be shown that the requirement of the Building Regulations can be met in other ways. Nevertheless, the great majority of buildings are designed to comply with the Building Regulations via the processes outlined in Approved Documents. For new buildings, the main documents are, for England:

- Part L1 2021 – Conservation of fuel and power, Volume 1: Dwellings[3]

- Part L2 2021 – Conservation of fuel and power, Volume 2: Buildings other than dwellings[4]

For Wales (from 23 November 2022):

- Part L1 2022 – Conservation of fuel and power, Volume 1: Dwellings – for use in Wales[5]

- Part L2A 2014 – Conservation of fuel and power in buildings other than dwellings – for use in Wales[6]

In Scotland (from December 2022) the equivalent documents are:

- Technical Handbook 2022 - Domestic Buildings - Section 6: Energy[7]

- Technical Handbook 2022 - Non Domestic Buildings - Section 6: Energy [8]

For Northern Ireland:

- Technical Booklet F1 - Conservation of fuel and power in dwellings: June 2022 [9]

- Technical Booklet F2 - Conservation of fuel and power in buildings other than dwellings – June 2022[10]

And for Ireland:

- Technical Guidance Document L - Conservation of Fuel and Energy – Buildings other than Dwellings[11]

- Technical Guidance Document L - Conservation of Fuel and Energy – Dwellings[12]

Although these regulations set slightly different targets, they all use a similar methodology for setting those targets. Part L (England) includes the following criteria for demonstrating compliance:

- Maximum allowable calculated CO2 emissions rate – the Target CO2 Emissions Rate

- Maximum allowable calculated primary energy rate – the target primary energy rate

- Limits on design flexibility including limiting fabric standards and limiting services efficiencies

- Maximum allowable airtightness

- Limiting the effects of heat gains in summer and heat losses in winter

- Ensuring that fixed building services meet specified efficiency requirements

- Ensuring the quality of construction and commissioning of fixed building services

- Providing information on the operation and maintenance of fixed building services to building owners

[top]Energy/CO2 requirement

The main requirement is that the calculated (predicted) CO2 emissions rate from the building as built, is less than or equal to the Target CO2 Emissions Rate and that the building primary energy rate is less than or equal to the target primary energy rate.

The calculated primary energy rate and the emission rate of CO2 is based on the annual energy requirements for space heating, water heating and lighting, less the emissions saved by renewable energy generation technologies and makes use of standard sets of data for different activity areas and call on common databases of construction and service elements.

For non-domestic buildings, the Building CO2 Emissions Rate (BER) must be less that the TER. The BER and TER are calculated using a monthly quasi-steady state energy balance methodology SBEM (Simplified Building Energy Model) based on BS EN ISO 52016-1[13], with lighting from BS EN 15193-1[14], or by using approved dynamic simulation modelling software such as IES-VE or TAS.

The SBEM software package produces a virtual model of the building. Standard operating conditions for each building type are defined in the National Calculation Methodology (NCM) and are applied to the building being assessed.

For residential buildings, the Dwelling CO2 Emissions Rate (DER) is calculated using the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP 2009), a monthly energy balance methodology.

These software packages produce a virtual model of the building. Standard operating conditions for each building type are defined in the National Calculation Method (NCM) and are applied to the building being assessed.

[top]Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs)

As part of its strategy to implement the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), the UK Government introduced Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) for all commercial and other non-domestic premises greater than 50m2 in April 2008.

EPC certificates give investors and occupiers the ability to make an accurate comparison of the energy efficiency of several commercial properties and compare the potential running costs before any purchasing or letting decisions are made.

The commercial EPC survey must be carried out by a qualified non domestic energy assessor (NDEA). The EPC is required when a building is constructed, let or sold and is valid for a period of 10 years or until a newer EPC is produced.

The EPC gives the theoretical (predicted) energy efficiency performance (the Asset Rating) of the building on a linear scale from A to G, where A is the most energy efficient, carbon neutral building. Each EPC is provided with an accompanying Recommendation Report providing options that could potentially improve the energy efficiency of the building and thereby the building’s individual EPC rating.

The A to G scale is a linear scale based on two key points defined as follows:

- The zero point on the scale is defined as the performance of the building that has zero net annual CO2 emissions associated with the use of the fixed building services as defined in the Building Regulations. This is equivalent to a Building Emissions Rate (BER) of zero.

- The border between grade B and grade C is set at the Standard Emissions rate (SER) and given an Asset Rating of 50. Because the scale is linear, the boundary between grades D and grade E corresponds to a rating of 100.

The SER is based on the actual building dimensions but with standard assumptions for fabric, glazing and building services, etc.

The Minimum Energy Efficiency Standard (MEES) came into force in England and Wales on 1 April 2018 and applies to private rented residential and non-domestic property. It aim is to encourage landlords and property owners to improve the energy efficiency of their properties by a restriction on the granting and continuation of existing tenancies where the property has an Energy Performance Certificate Rating lower than E.

[top]Display Energy Certificates (DECs)

First introduced in 2008, Display Energy Certificates (DECs) are required (since 2015) for buildings with a total useful floor area over 250m2 that are occupied by a public authority and frequently visited by the public. DECs for buildings between 250m2 - 1000m2 have a 10 year validity and DECs for building over 1000m2 have a validity of 1 year.

DECs show the actual energy usage of a building (over a 12-month period), the Operational Rating, and the relative performance of the building compared to a typical building of the same type. The Operational Rating is based on the energy consumption of the building as recorded by gas, electricity and other meters. The DEC should be clearly displayed at all times and clearly visible to the public. A DEC is always accompanied by an Advisory Report that lists cost effective measures to improve the energy rating of the building. The Advisory Report is valid for seven years.

As for EPCs, the DEC scoring system is based on an A to G scale. A building with performance equal to one typical of its type will have an Operational Rating of 100. A building that resulted in zero CO2 emissions would have an Operational Rating of zero, and a building that resulted in twice the typical CO2 emissions would have an Operational Rating of 200, etc.

[top]Climate Change Levy

The Climate Change Levy (CCL) is a tax on the taxable supply of specified energy products (taxable commodities) for use as fuels that is for lighting, heating and power, by all business consumers. CCL does not apply to taxable commodities supplied for use by domestic consumers or to charities for non-business use.

There are four groups of taxable commodities, as follows:

- Electricity

- Natural gas when supplied by a gas utility

- Liquid petroleum gas (LPG) and other gaseous hydrocarbons in a liquid state

- Coal and lignite; coke, and semi-coke of coal or lignite; and petroleum coke.

CCL is charged at a specific rate per unit of energy. There is a separate rate for each of the four categories of taxable commodity. The rates are based on the energy content of each commodity and are expressed in kilowatt-hours (kWh) for gas and electricity, and in kilograms for all other taxable commodities.

The rates are set by HM Revenue and Customs. Reduced rates are payable for participants in the Climate Change Agreement Scheme.

[top]BREEAM

The reduction of operational carbon emissions is a key requirement of BREEAM. Energy is the highest weighted section within BREEAM New Construction 2018[15] (16%) and there are mandatory operational carbon requirements to achieve ‘Excellent’ and ‘Outstanding’ ratings.

BREEAM sources data for the purpose of quantifying energy and greenhouse gas emissions from building energy modelling. This modelling must be carried out by design teams using approved software compliant with the UK's National Calculation Methodology (NCM).

Data sourced from the energy modelling are used to derive the Energy Performance Ratio which is a function of three metrics:

- Heating and cooling energy demand: This measures how well the building reduces heating and cooling energy demand

- Primary energy consumption: This measures how efficiently a building meets its energy demand

- Total resulting CO2 emissions: This measures the amount of carbon dioxide emissions the building emits when meeting its operational energy demands.

Modelled building performance, expressed as a percentage of the notional building level, is separately determined for the building’s modelled energy demand, consumption and CO2 emissions. The three individual ratios are then summed in to a single Energy Performance Ratio for New Constructions (EPRNC) through the use of weightings.

The weighted ratios of performance are totalled to give an overall EPRNC which is then compared to a table of benchmarks to determine the number of BREEAM credits awarded. The higher the EPRNC the better the performance and the higher the number of credits achieved.

[top]Energy Performance of Buildings Directive

The original Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD-1) was a core response to this target. When the Directive was adopted in December 2002 there were 160 million buildings in the EU, and it was anticipated that the Directive could deliver 45 million tonnes of carbon dioxide reduction by 2010.

By 2007 the EU had committed to even more stringent targets - in particular to a reduction of 20% in the EU’s total energy consumption by 2020, and a binding target for renewable energy of 20% of total supply by the same year. Individual Member States had also set their own national targets.

It was clear therefore that there was a need to strengthen the provisions of the Directive and a more thorough and rapid implementation. At the same time it was acknowledged that there had been a wide range of responses from Member States to the provisions of the original Directive, and that this variability should not be allowed to continue. Hence the second directive[16] (known as the ‘recast EPBD’ or EPBD-2) was drafted and adopted in May 2010, effectively replacing the original.

EPBD-2 covers a broad range of policies and supportive measures intended to help national EU governments boost energy performance of buildings and improve the existing building stock. Including:

- EU countries must establish strong long-term renovation strategies, aiming at decarbonising the national building stocks by 2050, with indicative milestones for 2030, 2040 and 2050. The strategies should contribute to achieving the national energy and climate plans (NECPs) energy efficiency targets

- EU countries must set cost-optimal minimum energy performance requirements for new buildings, for existing buildings undergoing major renovation, and for the replacement or retrofit of building elements like heating and cooling systems, roofs and walls

- all new buildings must be nearly zero-energy buildings (NZEB) from 31 December 2020. Since 31 December 2018, all new public buildings already need to be NZEB

- energy performance certificates must be issued when a building is sold or rented, and inspection schemes for heating and air conditioning systems must be established

- EU countries must draw up lists of national financial measures to improve the energy efficiency of buildings

The EPBD was last revised in 2018 with the objective of sending a strong political signal on the EU’s commitment to modernise the buildings sector in light of technological improvements and increase building renovations.

The revised EPBD covers a broad range of policies and supportive measures that will help national governments in the EU boost energy performance of buildings and improve the existing building stock in both a short and long-term perspective.

On 15 December 2021, the European Commission adopted a major revision (recast) of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD), as part of the ‘Fit for 55’ package. The latter consists of several legislative proposals to meet the new EU objective of a minimum 55 % reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030 compared to 1990. It is a core part of the European Green Deal, which aims to set the EU firmly on the path towards net zero GHG emissions (climate neutrality) by 2050.

The recast EPBD aims to accelerate building renovation rates, reduce GHG emissions and energy consumption, and promote the uptake of renewable energy in buildings. It would introduce a new EU definition of a ‘zero emissions building’, applicable to all new buildings from 2027 and to all renovated buildings from 2030. Zero-emissions buildings would need to factor in their life-cycle global warming potential. The recast EPBD would accelerate energy-efficient renovations in the worst performing 15 % of EU buildings, and would set minimum energy performance standards. In due course, every building would need to achieve at least a Class E on a revised A-G scale of energy performance certificates (EPCs). Other provisions introduce building renovation passports and a smart readiness indicator, end subsidies for fossil fuel boilers, and make building automation and control systems more widespread.

Under the European Union withdrawal Act 2018, EU directives, including the EPBD and the UK legislation that implements the EPBD, were retained as EU-derived domestic legislation. The UK Government has stated (2018) that the UK will continue to meet or improve upon EU requirements and will implement EU directives into domestic law.

[top]Renewable Heat Incentive

In March 2011, the Government launched the Renewable Heat Incentive (RHI) policy to revolutionise the way heat is generated and used. This is the first financial support scheme for renewable heat of its kind in the world. The aim of the scheme was to provide long-term financial support to renewable heat installations such as such as solar thermal technologies, biomass boilers and heat pumps, and to encourage the uptake of renewable heat. It will encourage the installation of renewable heat equipment.

The scheme was introduced in two phases:

- Domestic RHI – launched 9 April 2014 and open to homeowners, private landlords, social landlords and self-builders

- Non-domestic RHI – launched in November 2011 to provide payments to industry, businesses and public sector organisations

The RHI tariffs are tiered and are paid based on the heat output of the renewable energy system. For non-domestic systems, heat metering is required.

Following a review of the RHI in 2020, Government has confirmed that:

- the domestic RHI will close to new applicants on 31 March 2022, with its replacement - the Clean Heat Grant – taking effect in April 2022.

- the non-domestic RHI is to close to new applicants on 31 March 2021. The scheme will be replaced by a new mechanism, the Green Gas Support Scheme.

[top]Building assessment

Although currently there are no well-established methodologies for objectively quantifying and assessing all three aspects of sustainable construction (environmental, economic and social), there are accepted procedures and tools for assessing the environmental impacts of construction activities and buildings. Most of these are national and the most widely used tool in use in the UK, (BREEAM), is increasingly being used internationally.

In the UK, BREEAM (BRE Environmental Assessment Method) is the leading and most widely used environmental assessment method for buildings. It has become the de facto measure of the environmental performance of UK buildings. Although currently voluntary, many publically funded/procured buildings are required to have a minimum BREEAM rating. Many commercial building clients also recognise the benefits of procuring sustainable buildings and are increasingly using BREEAM to deliver sustainable buildings. BREEAM has certified over 200,000 buildings since it was first launched in 1990 although it is noted that by far the majority of these have been domestic houses.

BRE Global Limited is the scheme operator of BREEAM in the UK. A number of BREEAM versions are available, each designed to assess the sustainability performance of buildings, projects or assets at various stages in the life cycle. These include:

- BREEAM Communities for the master-planning of a larger community of buildings

- BREEAM New Construction: Buildings for new build, domestic and non-domestic buildings

- BREEAM New Construction: Infrastructure for new build infrastructure projects

- BREEAM In-Use for existing non-domestic buildings in-use

- BREEAM Refurbishment and Fit Out for domestic and non-domestic building fit-outs and refurbishments

The aim of BREEAM is to assess, encourage and reward environmental, social and economic sustainability throughout the built environment. The BREEAM schemes:

- encourage continuous performance improvement and innovation by setting and assessing against a broad range of scientifically rigorous requirements that go beyond current regulations and practice,

- empower those who own, commission, deliver, manage or use buildings, infrastructure or communities to achieve their sustainability aspirations,

- build confidence and value by providing independent certification that demonstrates the wider benefits to individuals, business, society and the environment

BREEAM consists of a number of best practice measures and performance standards that represent improvements in performance that can be implemented in a building. Measures are grouped into the following nine categories:

- Management - overall management policy, commissioning site management and procedural issues

- Health & Wellbeing - indoor and external issues affecting health and well-being

- Energy - operational energy and carbon dioxide (CO2) issues

- Transport - transport-related CO2 and location-related factors

- Water - consumption and water efficiency

- Materials - environmental implication of building materials, including life-cycle impacts

- Waste

- Land Use & Ecology - greenfield and brownfield sites, ecological value conservation and enhancement of the site

- Pollution - air and water pollution issues.

Each of the measures or ‘credits’ is either a mandatory, i.e. must be achieved for compliance, or voluntary. In addition, there are innovation credits which encourage exemplar performance or which recognise a building that innovates in the field of sustainable performance above and beyond the level currently rewarded by BREEAM .

Credits are weighted according to environmental category and then added together to produce a single overall score on a scale of Unclassified, Pass, Good, Very Good, Excellent and Outstanding. Building projects are assessed by registered assessors and reviewed by a third party (BRE Global) before being awarded a certificate.

Since 2008 it is compulsory under BREEAM to undertake a compulsory ‘Post Construction Review’ and to obtain a certificate at this stage. The Post Construction Review is based on ‘as built’ information and a site inspection of the completed building.

BREEAM is updated on a regular basis to reflect best performance and to make it compatible with other requirements, such as Part L of the Building Regulations. The current version is BREEAM 2018.

[top]Waste

As part of the Circular Economy Package adopted by the European Parliament in 2018, four Directives were amended and adopted. These were:

- The Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC)[17]

- The Landfilling Directive (1999/31/EC)[18]

- The Packaging Waste Directive (94/62/EC)

- The Directives on end-of-life vehicles (2000/53/EC), on batteries and accumulators and waste batteries and accumulators (2006/66/EC), and on waste electrical and electronic equipment (2012/19/EU)

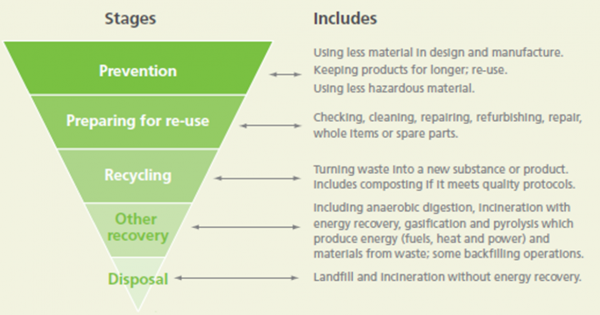

The overall goal of these directives is to improve EU waste management. This will contribute to the protection, preservation, and improvement of the quality of the environment as well as encourage the prudent and rational use of natural resources. More specifically, the directives aim to implement the concept of “waste hierarchy”, which has been defined in Article 4 of the Waste Framework Directive. The waste hierarchy sets a priority order for all waste prevention and management legislation and policy which should make any disposal of waste a solution the last resort.

The amendment to the Landfill of waste Directive (EU) 2018/850)[19] requires Member States to significantly reduce waste disposal by landfilling.

This will ensure that economically valuable waste materials are recovered through proper waste management and in line with the waste hierarchy. Member States will be required to ensure that, as of 2030, waste suitable for recycling or other recovery, in particular contained in municipal waste, will not be permitted to be disposed of to landfill. Use of landfills should remain exceptional rather than the norm.

The Waste Framework Directive[17] provides the legislative framework for the collection, transport, recovery and disposal of waste, and includes a common definition of waste. The directive requires all member states to take the necessary measures to ensure waste is recovered or disposed of without endangering human health or causing harm to the environment and includes permitting, registration and inspection requirements.

The directive also requires member states to take appropriate measures to encourage firstly, the prevention or reduction of waste production and its harmfulness and secondly the recovery of waste by means of recycling, re-use or reclamation or any other process with a view to extracting secondary raw materials, or the use of waste as a source of energy. The directive’s requirements are supplemented by other directives for specific waste streams.

2018 Amendments to the Waste Framework Directive (EU) 2018/851)[19] require Member States to improve their waste management systems into the management of sustainable material, to improve the efficiency of resource use, and to ensure that waste is valued as a resource.

Specifically relating to construction and demolition waste the Directive requires:

- Member States to take measures to promote selective demolition in order to enable removal and safe handling of hazardous substances and facilitate re-use and high-quality recycling by selective removal of materials, and to ensure the establishment of sorting systems for construction and demolition waste at least for wood, mineral fractions (concrete, bricks, tiles and ceramics, stones), metal, glass, plastic and plaster.’

- By 31 December 2024, the Commission shall consider the setting of preparing for re-use and recycling targets for construction and demolition waste and its material-specific fractions

The Waste Framework Directive[17] requires the UK to design and implement waste prevention programmes and sets the challenging target to reuse and recycle 70% of construction and demolition waste by 2020. Such programmes will need to take account of the following five-step hierarchy:

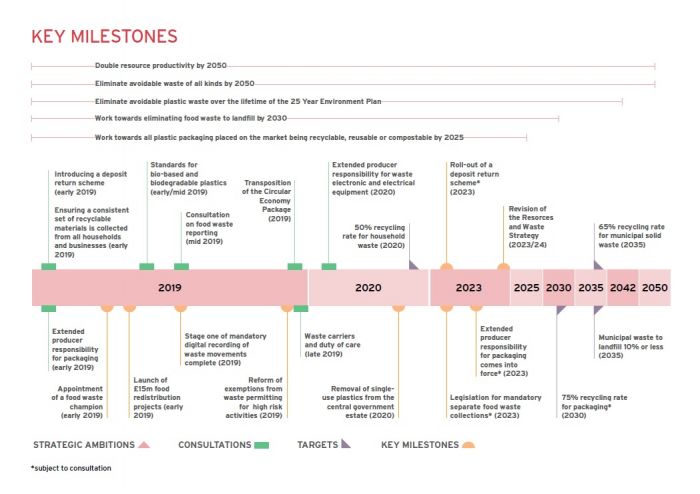

Reducing waste is a priority for the UK Government. In 2018, UK Government published a new strategy for waste and resources in England[20]. Importantly the strategy has broadened from just waste management to consider wider resource issues. The strategy has the two overarching objectives:

- To maximise the value of resource use;

- To minimise waste and its impact on the environment.

The strategy includes policies, actions and commitments based on the following five strategic principles:

- To provide the incentives, through regulatory or economic instruments if necessary and appropriate, and ensure the infrastructure, information and skills are in place, for people to do the right thing;

- To prevent waste from occurring in the first place, and manage it better when it does;

- To ensure that those who place on the market products which become waste to take greater responsibility for the costs of disposal – the ‘polluter pays’ principle;

- To lead by example, both domestically and internationally; and

- To not allow our ambition to be undermined by criminality.

Key milestones from the strategy are shown in the figure (below)

Specifically in relation to construction, the strategy includes initiatives by the Green Construction Board to develop guidance for increasing resource efficiency and reducing waste through the adopting of circular economy principles. The Green Construction Board has published a report on the interpretation of zero avoidable construction waste and work is underway to develop a roadmap setting out how and when this can be achieved.

[top]Duty of Care Regulations

Construction companies have a legal ‘duty of care’ with respect to any waste that they generate on site. This duty applies to anyone who produces, imports, transports, stores, treats or disposes of controlled waste from business or industry. Commercial, industrial and household wastes (including hazardous/special wastes) are classified as ‘controlled waste’. The duty of care also applies to anyone who acts as a waste broker. Companies must ensure that:

- Their waste is stored, handled, recycled or disposed of safely and legally

- Their waste is stored, handled, recycled or disposed of only by businesses which hold the correct, current licence to do the work

- They record all transfers of waste between their and another business, using a waste transfer note (WTN) signed by both businesses

- They keep all WTNs for at least two years

- They record any transfer of hazardous/special waste between their business and another business, using a consignment note signed by both businesses

- They keep all consignment notes for at least three years.

If the company is a sub-contractor and the main contractor arranges for the recovery or disposal of waste that they produce, the sub-contractor is still responsible for those wastes under the duty of care.

This duty of care has no time limit. It extends until the waste has either been finally disposed of or fully recovered.

If companies produce or deal with waste that has certain hazardous properties, they will also have to comply with the hazardous/special waste regulations.

[top]Hazardous/Special Waste Regulations

Waste that has hazardous properties which may make it harmful to human health or the environment is known as hazardous waste in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and special waste in Scotland.

The definition of hazardous/special waste is relatively wide and covers objects that contain hazardous substances such as televisions and fluorescent light tubes. As a result, many companies are likely to produce some form of waste that is hazardous and need to deal with it accordingly. Hazardous waste is classified using the European Waste Catalogue.

The environmental regulator, the Environment Agency in England and Wales, tracks the movement of hazardous waste through the consignment note system. This ensures that waste is managed responsibly from where it is produced until it reaches an authorised recovery or disposal facility. Companies must ensure that all hazardous waste is stored and transported with the correct packaging and labelling.

Hazardous waste can only be disposed of at a landfill site that is authorised to accept it. Some landfill sites that are classified as non-hazardous may be able to take certain stable non-reactive hazardous wastes if they have the appropriate facilities. A landfill site authorised to accept hazardous waste may not be able to take all types of hazardous waste.

Hazardous waste must be treated, before it can be sent to landfill, to meet the limits set by a landfill site's waste acceptance criteria (WAC). Treatment means physical, thermal, chemical or biological processes, including sorting, that change the characteristics of the waste in order to:

- Reduce its volume

- Reduce its hazardous nature

- Make it safe to handle

- Make it easier to recover.

For further information on current legislation with respect to construction waste see the Environment Agency guidance.

[top]Landfill Tax and Aggregates Levy

Introduced in 1996, the Landfill Tax remains the primary fiscal incentive to encourage waste producers and the waste management industry to switch to more sustainable alternatives for disposing of material. The tax has risen steadily since 1996, in line with inflation and, from April 2020, the standard rate is £94.15 per tonne. A lower rate of £3 per tonne applies to inactive (or inert) waste.

Reflecting the large volume of aggregates consumed by the construction industry (over 200 Mt pa), the Aggregates Levy was introduced in 2002 to reduce demand for primary aggregates and to encourage the use of recycled and secondary aggregates. The levy is currently £2.00 per tonne of primary aggregates. The tax is payable on sand, gravel or rock that has either been quarried, dredged or imported.

[top]Site Waste Management Plans Regulations (SWMP)

Effective construction site waste management is a key tool for improving efficiency and reducing waste. Introduced in April 2008, the SWMP Regulations [21] made it compulsory to develop and implement SWMPs on construction projects costing more than £300k. Defra guidance advises that a SWMP should:

- Identify the different types of waste that will be produced by the project, and note any changes in the design and the materials specification that seek to minimise this waste

- Consider how to re-use, recycle or recover the different wastes produced by the project

- Require the construction company to demonstrate that it is complying with the duty of care regime

- Record the quantities of waste produced.

The Regulations also required a more detailed analysis to be conducted on projects costing more than £500k.

Although the Site Waste Management Plans Regulations Act 2008 was repealed on the 1st December 2013 as part of Government’s Red Tape Challenge, SWMPs continue to be used on many construction sites and by responsible contractors.

[top]BREEAM

BREEAM is BRE’s Environmental Assessment Method for buildings. Under BREEAM, credits are awarded under a number of environmental categories, one of which is waste, and the buildings rated according to its total score.

Under BREEAM New Construction 2018 (UK)[15] the following waste issues are assessed:

- Wst 01 Construction waste management (7 credits)

Improving resource efficiency through developing a pre-demolition audit and a Resource Management Plan, maximising the recovery of material during demolition and diverting non-hazardous waste from landfill. - Wst 02 Use of recycled and sustainably sourced aggregates (1 credit)

Encouraging the use of recycled or secondary aggregate or aggregate types with lower environmental impact to reduce waste and optimise material efficiency. - Wst 03 Operational waste (1 credit)

Encouraging the diversion of operational waste form landfill through the provision of space and facilities allowing the segregation and storage of recyclable waste. - Wst 04 Speculative finishes, Offices only (1 credit)

Specification of floor and ceiling finishes only where agreed with the occupant or, for tenanted areas where the future occupant is unknown, installation in a show area only, to reduce wastage. - Wst 05 Adaptation to climate change (1 credit)

Encouraging consideration and implementation of measures to mitigate the impact of more extreme weather conditions arising from climate change over the lifespan of the building. - Wst 06 Design for disassembly and adaptability (2 credits)

Encouraging consideration and implementation of measures design options related to functional adaptability and disassembly, which can accommodate future changes to the use of the building and its systems over its lifespan.

BREEAM does not specifically address any issues in connection with demolition waste reduction or management although credit Wst 02 does encourage the use of recycled and secondary aggregates.

The most highly weighted waste issue under BREEAM is Construction waste management (Wst 01) under which credits are awarded according to the benchmarks shown in the table.

| BREEAM credits | Amount of waste generated per 100m2 (gross internal floor area) | |

|---|---|---|

| Volume (m3) | Weight (tonnes) | |

| One credit | ≤13.3 | ≤11.1 |

| Two credits | ≤7.5 | ≤6.5 |

| Three credits | ≤3.4 | ≤3.2 |

| Exemplary level | ≤1.6 | ≤1.9 |

[top]Construction materials

Greater attention is being paid to the sustainability credentials of the materials used to construct buildings although there are currently no mandatory regulatory requirements. In particular, as the regulated operational carbon emissions of buildings are reduced, greater attention is being placed on the embodied carbon impacts of construction materials and products.

[top]Carbon foot-printing

Carbon foot-printing or embodied carbon assessment is increasingly being used within the construction industry to inform building design and product selection. Although this is currently on a voluntary basis, it is likely that some form of regulation, possibly via Part L of the Building Regulations, will be introduced in the future.

Reflecting the rapid growth in carbon foot-printing, there are many competing standards. The most respected standards include:

- PAS 2050 Specification for the assessment of the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of goods and services[22]

- BS EN ISO 14064[23] – in three parts, this standard provides advice on measuring, quantifying and reducing greenhouse gas emissions

- GHG Protocol standards[24].

A carbon footprint tool for buildings is available.

[top]CEN standards on the sustainability assessment of buildings

In response to the plethora of different sustainability schemes being developed in Europe, the European Commission issued a mandate to the European Committee for Standardisation (CEN) to development horizontal standardised methods for the assessment of the integrated environmental performance of buildings. Subsequently the remit was broadened to include social and economic dimensions.

European Standards Technical Committee CEN/TC350 and its various working groups, began work in 2005 and a suite of standards have been developed. These include:

- BS EN 15643-1[25]

- BS EN 15643-2[26]

- BS EN 15643-3[27]

- BS EN 15643-4[28]

- BS EN 15804[29]

- BS EN 15978[30]

- BS EN 16309[31].

BS EN 15804[29] provides core product category rules (PCR) for Type III Environmental Product Declarations (EPD) for any construction product and construction service. The core PCR:

- Defines the parameters to be declared and the way in which they are collated and reported

- Describes which stages of a product’s life cycle are considered in the EPD and which processes are to be included in the life cycle stages

- Defines rules for the development of scenarios

- Includes the rules for calculating the Life Cycle Inventory and the Life Cycle Impact Assessment underlying the EPD, including the specification of the data quality to be applied

- Includes the rules for reporting predetermined, environmental and health information, that is not covered by LCA for a product, construction process and construction service where necessary

- Defines the conditions under which construction products can be compared based on the information provided by EPD. For the EPD of construction services the same rules and requirements apply as for the EPD of construction products.

The importance of European Standards is that EU Member States, including the UK, have to use European Standards where they exist when regulating and National Standards must be withdrawn if they are in conflict with European Standards. So if the UK decides to regulate on measuring the sustainability of buildings and construction products then the UK will have to use the CEN/TC350 standards.

[top]Responsible sourcing

There is a growing demand within construction supply chains to demonstrate that materials, products and services are being responsibly sourced. Producers are required to demonstrate their credentials to contractors who, in turn, need to show their clients that their buildings have been responsibly procured and resourced.

Responsible sourcing of construction products is included within the Government’s 2008 Sustainable Construction Strategy[32] which includes the target to develop Framework Standards to facilitate the development of sector Responsible Sourcing schemes. Since 2008, two standards have been produced: BES 6001[33] and BS EN 8902[34].

- Developed by BRE, BES 6001[33] provides a framework against which all construction products may be assessed. The framework comprises a number of criteria setting out the requirements of an organisation in managing the supply of construction products in accordance with a set of agreed principles of sustainability, the precise scope of which is determined by stakeholder engagement.

- BS 8902[34] gives requirements for the management, development, content and operation of sector certification schemes for responsible sourcing and supply of construction products

Responsible Sourcing is also included within BREEAM New Construction 2018[15]. All materials used to construct a building are assessed for the level of certification achieved. Recognised schemes include BES 6001[33], environmental managements systems (EMS) such as ISO 14001[35] and Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) certification. The full list of responsible sourcing schemes recognised by BREEAM is given in BREEAM Guidance note 18].

[top]Planning requirements

The UK planning system has an important and overarching role in delivering sustainable development. The aim of the planning system is to help ensure that development takes place in the public interest and in economically, socially and environmentally sustainable ways. It also has a role to play in helping to cut carbon emissions, protect the natural environment and deliver energy security.

The core elements of the National Planning Policy Framework[36] are development plan-making and development management. These activities are primarily undertaken at the local level. Plans and decisions should apply a presumption in favour of sustainable development

The planning system in England requires each local planning authority to prepare a local development framework (LDF) which outlines how planning will be managed for that area. In determining planning applications, local planning authorities (usually the district or borough council) must have regard to their LDF.

Planning authorities are also responsible for development management. This includes statutory requirements on publicising, consulting on and determining most applications for planning permission, taking into account the opinions of local people and others.

The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government supports plan-making and development management, principally through the provision of planning legislation, national planning policy and guidance.

The National Planning Policy Framework[36], first published in March 2012, effectively replaced all previous Planning Policy Statements (PPS).The framework gives guidance to local councils in drawing up local plans and on making decisions on planning applications. It states that Local Plans should be based upon and reflect the presumption in favour of sustainable development, with clear policies that will guide how the presumption should be applied locally. The current National Planning Policy Framework[36] was published in 2019.

Most planning policy relates to relatively high-level decision making such as where and if new development should be permitted. At the local level however, many planning authorities have prepared supplementary planning guidance (SPG) and supplementary planning documents (SPD) which provide more detailed guidance applicable at the individual project level; guidance can be either topic or site specific.

SPGs and SPDs are one of the 'material considerations' taken into account when determining planning applications. Most planning authorities are replacing SPG with SPDs which form part of the authorities’ Local Development Framework.

Many local planning authorities have prepared SPG/SPD that specifically address sustainable design and construction. In terms of scope these documents are often closely aligned with national assessment schemes such as BREEAM, however many documents vary significantly between different authorities and many include different issues and targets. In terms of material selection, most documents refer to the Green Guide to Specification ratings as the means of assessing environmental impact.

[top]Construction Sector Deal

Part of the UK’s Industrial Strategy, the Construction Sector Deal[37] was published in 2019. This policy paper provides a framework intended to deliver:

- a 33% reduction in the cost of construction and the whole life cost of assets

- a 50% reduction in the time taken from inception to completion of new build

- a 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in the built environment –supporting the Industrial Strategy’s Clean Growth Grand Challenge

- a 50% reduction in the trade gap between total exports and total imports of construction products and materials

Specifically in terms of the sustainability, the Construction Sector Deal[37] sets out to adopt new information management measures, digital and manufacturing technologies that will enable the precision design and modelling of buildings, improve project management of construction projects and facilitate the incorporation of new technologies, such as sensors, smart systems and materials into built assets.

Using innovative and more efficient technologies in infrastructure will help deliver the Buildings Mission objective of at least halving the energy use of new buildings by 2030. The Mission will make more sustainable and lower carbon buildings cheaper to build, and give those who occupy buildings greater control over the energy they use. It will help to improve the environment through significantly reducing the costs of retrofitting these technologies within existing buildings, reducing their energy consumption and increasing their sustainability.

More efficient processes will also help to minimise waste, reducing the current volume of approximately 120 million tonnes a year produced by construction, demolition and excavation, which accounts for nearly 60% of all UK waste. Using innovative and more efficient technologies in infrastructure will complement the Clean Growth Grand Challenge identified in the Industrial Strategy[37].

[top]Climate emergency declarations

Reflecting the urgency to address climate change, parts of the UK construction industry are taking a lead and declaring a climate change emergency. Globally, the WGBC has launched the Net Zero Carbon Buildings Commitment which challenges business, organisations, cities, states and regions to reach net zero carbon in operation for all assets under their direct control by 2030, and to advocate for all buildings to be net zero carbon in operation by 2050.

Specifically in the UK:

The IStructE has launched Structural engineers declare climate and biodiversity emergency. Signatories are required to sign-up to 11 commitments to show leadership and drive real improvements to help address the climate emergency within their professional capacity as structural engineers. IStructE climate emergency resources for structural engineers are available here.

RIBA has developed the 2030 Climate Challenge[38] to help architects meet net zero (or better) whole life carbon for new and retrofitted buildings by 2030. It sets a series of targets for practices to adopt to reduce operational energy, embodied carbon and potable water.

The 2030 Climate Challenge[38] targets take account of the latest recommendations from the Green Construction Board and include:

- Reduce operational energy demand by at least 75%, before offsetting

- Reduce embodied carbon by at least 50-70%, before offsetting

- Reduce potable water use by at least 40%

- Achieve the RIBA 2030 Challenges core health and wellbeing targets on temperature, daylight and indoor air quality

RIBA chartered practices can sign up to the climate challenge here.

The Institution of Civil Engineers has developed a Sustainability route map and is inviting civil engineering practices operating in the UK to sign up to a declaration to deliver a net-zero infrastructure.

[top]References

- ↑ Construction 2025, Industrial Strategy: government and industry in partnership, BIS, July 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 TM63 Operational performance: Building performance modelling, CIBSE, 2020

- ↑ Approved Document L1, 2021, Conservation of fuel and power, Volume 1: Dwellings. Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

- ↑ Approved Document L2, 2021, Conservation of fuel and power, Volume 2:Buildings other than dwellings. Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

- ↑ Approved Document L1, 2022, Conservation of fuel and power, Volume 1: Dwellings – for use in Wales. Welsh Government

- ↑ Approved Document L2A,(Conservation of fuel and power (New buildings other than dwellings) 2014 Edition incorporating 2016 amendments. Welsh Government

- ↑ Building standards technical handbook: 2022 - Domestic Buildings, Section 6: Energy, The Scottish Government

- ↑ Building standards technical handbook: 2022 - Non Domestic Buildings, Section 6: Energy, The Scottish Government

- ↑ Technical Booklet F1 - Conservation of fuel and power in dwellings: June 2022, Department of Finance (NI)

- ↑ Technical Booklet F2 - Conservation of fuel and power in buildings other than dwellings – June 2022, Department of Finance (NI)

- ↑ Building Regulations: Technical Guidance Document L Conservation of Fuel and Energy – Buildings other than Dwellings, Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage, 2021

- ↑ Building Regulations: Technical Guidance Document L Conservation of Fuel and Energy – Dwellings, Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage, 2021

- ↑ BS EN ISO 52016-1:2017 Energy performance of buildings. Energy needs for heating and cooling, internal temperatures and sensible and latent heat loads. Calculation procedures, BSI

- ↑ BS EN 15193-1:2017 Energy performance of buildings. Energy requirements for lighting. Specifications, Module M9, BSI

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 BREEAM UK New Construction, Non-domestic buildings (All UK), Technical Manual, SD5078: BREEAM New construction 2018 1.0. BRE Global Ltd.

- ↑ Directive 2010/31/Eu Of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 May 2010 on the energy performance of buildings (recast)

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Directive 2008/98/EC Of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on waste and repealing certain Directives

- ↑ Council Directive 1999/31/EC of 26 April 1999 on the landfill of waste

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Directive (EU) 2018/850 of The European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive 1999/31/EC on the landfill of waste

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Our waste, our resources: A strategy for England 2018, Defra, HMSO

- ↑ The Site Waste Management Plans Regulations 2008 Statutory Instrument No. 314, 2008

- ↑ PAS 2050:2011 - Specification for the assessment of the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of goods and services, BSI.

- ↑ BS EN ISO 14064-1:2019 Greenhouse gases. Specification with guidance at the organization level for quantification and reporting of greenhouse gas emissions and removals. BSI

- ↑ The Greenhouse Gas Protocol - A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard (Revised Edition), World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) and World Resources Institute

- ↑ BS EN 15643-1:2011 - Sustainability of construction works - Sustainability assessment of buildings - Part 1: General framework. BSI

- ↑ BS EN 15643-2:2011 - Sustainability of construction works - Assessment of buildings - Part 2: Framework for the assessment of environmental performance. BSI

- ↑ BS EN 15643-3:2012 Sustainability of construction works. Assessment of buildings. Framework for the assessment of social performance. BSI

- ↑ BS EN 15643-4:2012 Sustainability of construction works. Assessment of buildings. Framework for the assessment of economic performance. BSI

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 BS EN 15804:2012+A2 2019 - Sustainability of construction works - Environmental product declarations - Core rules for the product category of construction products. BSI

- ↑ BS EN 15978:2011 - Sustainability of construction works - Assessment of environmental performance of buildings - Calculation method. BSI

- ↑ BS EN 16309:2014+A1:2014 - Sustainability of construction works - Assessment of social performance of buildings - Calculation methodology. BSI

- ↑ Strategy for Sustainable Construction; Department for Business, Enterprise & Regulatory Reform. June 2008

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 BES 6001: ISSUE 3.1 Framework Standard for the Responsible Sourcing of Construction Products, BRE Environmental & Sustainability Standard, 2016

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 BS 8902:2009 Responsible sourcing sector certification schemes for construction products. Specification, BSI

- ↑ BS EN ISO 14001:2015 Environmental management systems. Requirements with guidance for use. BSI

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 National Planning Policy Framework, Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, February 2019. HMSO

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 Industrial Strategy, Construction Sector Deal, BEIS, 2018, HMSO

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge, Royal Institute of British Architects 2019.

[top]Resources

- Carbon footprint tool for buildings

- Steel construction – Sustainable Procurement

- Steel construction – Carbon Credentials

- Target Zero – Cost effective routes to carbon reduction

Target Zero design guides:

- Guidance on the design and construction of sustainable, low carbon office buildings

- Guidance on the design and construction of sustainable, low carbon warehouse buildings

- Guidance on the design and construction of sustainable, low carbon supermarket buildings

- Guidance on the design and construction of sustainable, low carbon mixed-use buildings

- Guidance on the design and construction of sustainable, low carbon school buildings

[top]See also

- Construction and demolition waste

- Recycling and reuse

- Life cycle assessment and embodied carbon

- Operational carbon

- BREEAM

- Target Zero

- Steel and the circular economy

[top]External links

- European Committee for Standardisation, CEN

- The CRC Energy Efficiency Scheme

- BREEAM

- WRAP:construction waste management