The Curve cultural and learning centre, Slough

Article in NSC February 2015

Steel lends itself to curving library

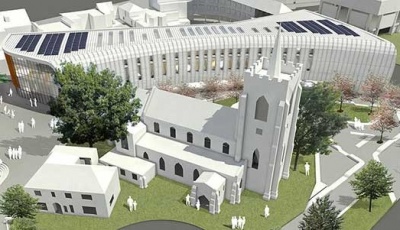

The centrepiece of Slough’s town centre regeneration scheme is a highly architectural and uniquely shaped steel-framed library and cultural centre.

More than 10 years of planning work are coming to fruition as a multi-million pound regeneration scheme is now beginning to transform Slough town centre.

The Heart of Slough project has already delivered a new iconic bus station and the scheme will eventually revitalise the town with new office and residential developments as well as infrastructure improvements to make the area more pedestrian friendly. The scheme’s flagship development is the Curve cultural and learning centre, currently under construction and scheduled for completion this autumn (2015).

As the name suggests the structure is a steel-framed curved rectangle in shape and plan. Each of the building’s elevations feature either cantilevers or sloping and curving façades, with the main north side presenting the most striking aspect with a long sweeping, predominantly glazed, elevation looking on to the adjacent listed St Ethelbert’s Church.

The three level building is 89.7m long, 15.5m high and has a width, which is 34m at its maximum and 16.5m at its narrowest. With an overall floor space of 4,500m2, the centre will include a library, café, office space and a 280-seat performance space.

Constructing a building with this kind of complex shape brings with it a whole host of geometry and setting out challenges. The use of a BIM model, shared between the entire project team, made the design process less onerous. “Our expertise in BIM and 3D modelling using Tekla software has been a great benefit on this project, enabling us to integrate the original architect’s model with our own,” says Caunton Engineering Contracts Manager, Phil Ratcliffe.

Peter Brett Associates Project Engineer, Mark Way adds: “BIM was the best solution as it allowed everyone to see the same model and this made it possible to detect any possible problems well in advance. Referring to why structural steelwork was chosen as the project’s framing material he adds: “Using steelwork made it much easier to design and form such a challenging shape.”

Initially the Curve was to be built with reinforced concrete, but a redesign of the project, instigated by main contractor Morgan Sindall and involving Peter Brett Associates, resulted in the frame changing to structural steelwork. Not only did this make the project quicker to build it also made the overall frame lighter, saving the client money as shallower piled foundations were needed.

Once foundation installation and groundworks were completed the steelwork programme began in August and was completed in November. Caunton Engineering erected the structure from east to west but, before the programme reached the final few bays, the company realised as the site is quite confined the partially complete frame would begin to obstruct the only access point for steel deliveries.

This could have been a logistical headache if it were not for the fact that there was just enough space for Caunton to stockpile the final 30t or so of steel. “Once we had the steel stockpiled we also had just enough room to position our 50t capacity mobile crane,” says Mr Ratcliffe.

Stability for the frame is derived from bracing located in stairwells and the lift cores. Early in the erection programme, temporary bracing was also installed to add further stability while the frame was being erected. These temporary props were only removed once the first and second floor concrete toppings had been cast, as this then provided the necessary composite stability/action.

The structure’s perimeter columns are spaced at 7.5m intervals, but internally this grid pattern has not been adhered to because of two large atriums that pierce the first and second level floor plates. Most of the internal columns are CHS members, chosen for aesthetic reasons, as they will remain exposed within the completed building. “The atriums mean we have some beams spanning up to 12m and so we had to limit movement due to wind effects by installing tie beams at first floor level,” explains Mr Way.

Creating the feature north façade of the building is a series of curved rib columns supported off a curving 323mm diameter tubular member.

This main supporting tubular beam curves its way along the entire 89m-long façade, supported on sloping RHS columns. Below the tubular section the façade will be predominantly glazed and consequently tolerances were a challenge on this part of the job.

Specialist bending contractor Barnshaw Section Benders bent all of the ribs and the curved tube. The ribs were delivered to site in complete sections, requiring no splices to form the façade. These ribs vary in height up to 9m, depending on where they are located along the curving tubular section.

As the tubular section’s curvature changes radius along its length it was also brought to site in various lengths. In order to give the tubular section a seamless appearance once the project is complete, the various lengths are connected via internal bolts that are hidden behind plates which were retro welded into place.

The southern façade is less complex and straight in plan, although it does have a bullnose feature where the perimeter columns curve at the top (similar to large hockey sticks) to form the connection with the roof. “The interface between the roof and the façade steelwork was one of the main design challenges as the roof pitches at three angles,” explains Mr Way.

Summing up, Morgan Sindall Senior Project Manager, Alistair Kendall says: “Morgan Sindall is working within Slough Borough Council’s Local Asset Backed Vehicle and a key project within this is The Curve. We are well versed in delivering complex and innovative structures, the latest of which is this new library and community centre for Slough. The design of The Curve will make it a local landmark and we’re very excited to be leading such an iconic project.”

Entrance truss

The Curve will have public entrances at both ends, with the western end also incorporating a 7m-high void to allow vehicles to access a service yard located at the rear of the building. To create this open space a 6m high Vierendeel truss, supported on a V-shaped galvanized oval section column, is positioned along the perimeter of the building. The truss had to be brought to site piece small, as it would have been too large to transport to site fully assembled. Once at the project the truss was erected piece by piece as there was not enough room on site to assemble it on the ground.

Redesign of project

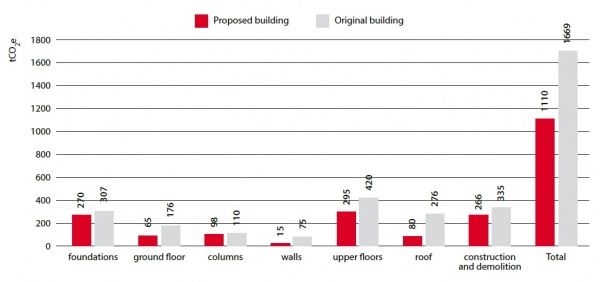

Peter Brett Associates carried out an embodied carbon calculation to test the assumption that they had improved the amount of embodied energy contained within the structural frame in relation to the original design. As the graph below shows they calculated that a saving of 35% of CO2e emissions has been made as a result of the building and frame being redesigned in steel instead of reinforced concrete.

Embodied carbon

By Michael Sansom (SCI)

As new buildings become more energy efficient in operation, greater attention is turning to the embodied carbon of construction products and materials. As a reminder, embodied carbon is the summation of all the global warming gases emitted as a consequence of winning, transporting and processing construction materials.

Although methodologies for assessing and comparing embodied carbon impacts are still evolving, better and more comprehensive data are enabling more robust and comprehensive assessment of buildings – such as was done by Peter Brett Associates on the Curve project.

In keeping with the need to move towards a more circular economy, more thought is being given to what happens to buildings when they are deconstructed so that more materials are retained within the economy rather than lost to landfill or downcycled into low grade applications. This is being done by including the impacts of demolition, transport and processing of demolition waste and the disposal or beneficial reuse and recycling of products and materials.

All construction materials are not equal in this aspect. Steel is unmatched in terms of its inherent recyclability and, in the case of structural steel, its potential reusability. These future benefits are real, are consistent with circular economy principles and should be factored into embodied carbon assessments.

Data to enable practitioners to undertake whole life embodied carbon comparisons for the most common structural materials are already available. Advice and data are available in the Life cycle assessment and embodied carbon article on SteelConstruction.info. The timber sector has published environmental product declarations (EPDs) on common timber products and the concrete sector is due to publish comparable data shortly.

The Curve project also demonstrates the knock-on embodied carbon benefits that are achievable by choosing a steel frame. Undertaking an holistic assessment of the whole building, rather than just comparing different framing options, consequential benefits in terms of speed of construction, fewer deliveries to site, lighter foundations, etc. are accounted for. In addition to cost savings, these benefits reduce the overall embodied carbon of the project – as shown in the graph in the main article.

The use of BIM was key to the success of the Curve project. Work is under way to integrate embodied carbon data within BIM models and looking ahead, this will enable embodied carbon assessments to be undertaken more quickly and accurately by design teams.

| Architect | Bblur |

| Structural Engineer | Peter Brett Associates |

| Steelwork Contractor | Caunton Engineering |

| Main Contractor | Morgan Sindall |

| Main Client | Slough Borough Council |